What Doing Something Actually Looks Like

How Minneapolis is showing us the way.

I watched the video of Alex Pretti’s murder by accident.

I was in my kitchen making coffee, spilling beans as I moved too fast, trying to buy myself sixty seconds before returning to my four-year-old. We were fifty-five minutes into playing superheroes — his current obsession — and I was grabbing a quick caffeine boost before stepping back into my role as Iron Man.

I opened Instagram to see what was going on in Minneapolis, a practice that had become habit as the federal government kept sending ICE officers there in droves. The video was at the top of my feed.

At first it didn’t register as what it was. A man holding a phone, helping a woman up from the ground. Then a rush of uniformed men. I watched, transfixed, as they knocked him down. As they hit him. As pepper spray bloomed in the air. And then, while he was on the ground, they fired into him.

I went hot and cold at the same time. The kitchen felt too bright. I was holding my breath, my arm braced against the counter.

My son ran in and tugged at my leg, impatient. I was taking too long. Spider-Man was waiting.

I put the phone down. I looked at him and tried to come back to the room — to become Iron Man again — but something in me had shifted. A bolt through my nervous system. And the only thought I could hold onto was this:

I have to do something.

The next day, a blizzard hit the Northeast — the biggest snowstorm we’ve had since I was a kid. And my little street did what my little street does in weather like that: we showed up.

Neighbors who usually offer hurried waves on their way to work became people who lingered. People who checked in. A few different folks knocked on our 94-year-old neighbor’s door to make sure she was okay. My husband shoveled for a neighbor recovering from surgery. I ran out while the roads were still drivable and got everyone bagels. A guy with a plow did the ends of all our driveways, the hard-packed parts that feel impossible with a shovel. A friend texted asking for two eggs so she could make bread because she couldn’t get to the store.

It wasn’t dramatic. It was ordinary. It was practical. It was care.

And it felt so good. Not because a snowstorm is good (it isn’t), but because being connected is. Because for a few hours, we weren’t alone in our houses staring at our phones, absorbing catastrophe. We were in motion. We were looking out for each other.

That’s when it hit me: this is what doing something actually looks like. And it’s exactly what people in Minnesota are doing right now. Keeping each other safe.

I called my best friend Kim in Minneapolis to help me understand what doing something right now can actually look like — beyond rage, beyond internet activism, beyond that familiar sense of helplessness when the threat feels too big.

Kim is not, as we traditionally define them, a superhero. She’s a mom. A professor. An ordinary person who wanted to help. Over the past several weeks, she’s become her son’s public school Sanctuary School Team lead — part of a parent-led effort inside Minneapolis public schools focused on preparedness, practical support, and showing up for families most impacted. She’s also spent months as a courtroom observer in immigration cases.

I asked her: How do you start? What do you do first? What actually helps? How do you build something that feels doable — something people can join without needing to be experts or full-time organizers or saints?

Kim told me she was moved to action after hearing from people she trusted in immigrant rights work that they needed to prepare for an uptick in ICE activity. And she listened.

She didn’t know what she would do. She didn’t have a plan. But she showed up to a Zoom call about organizing a Sanctuary School Team — a model already used in other cities to coordinate support around schools if families suddenly felt unsafe traveling, showing up, or asking for help.

After that, she started a Signal channel. For a week, she was the only person in it.

She laughed when she told me this — how awkward it felt. But she kept going anyway, because waiting for certainty felt riskier than beginning imperfectly. That choice shaped everything that followed.

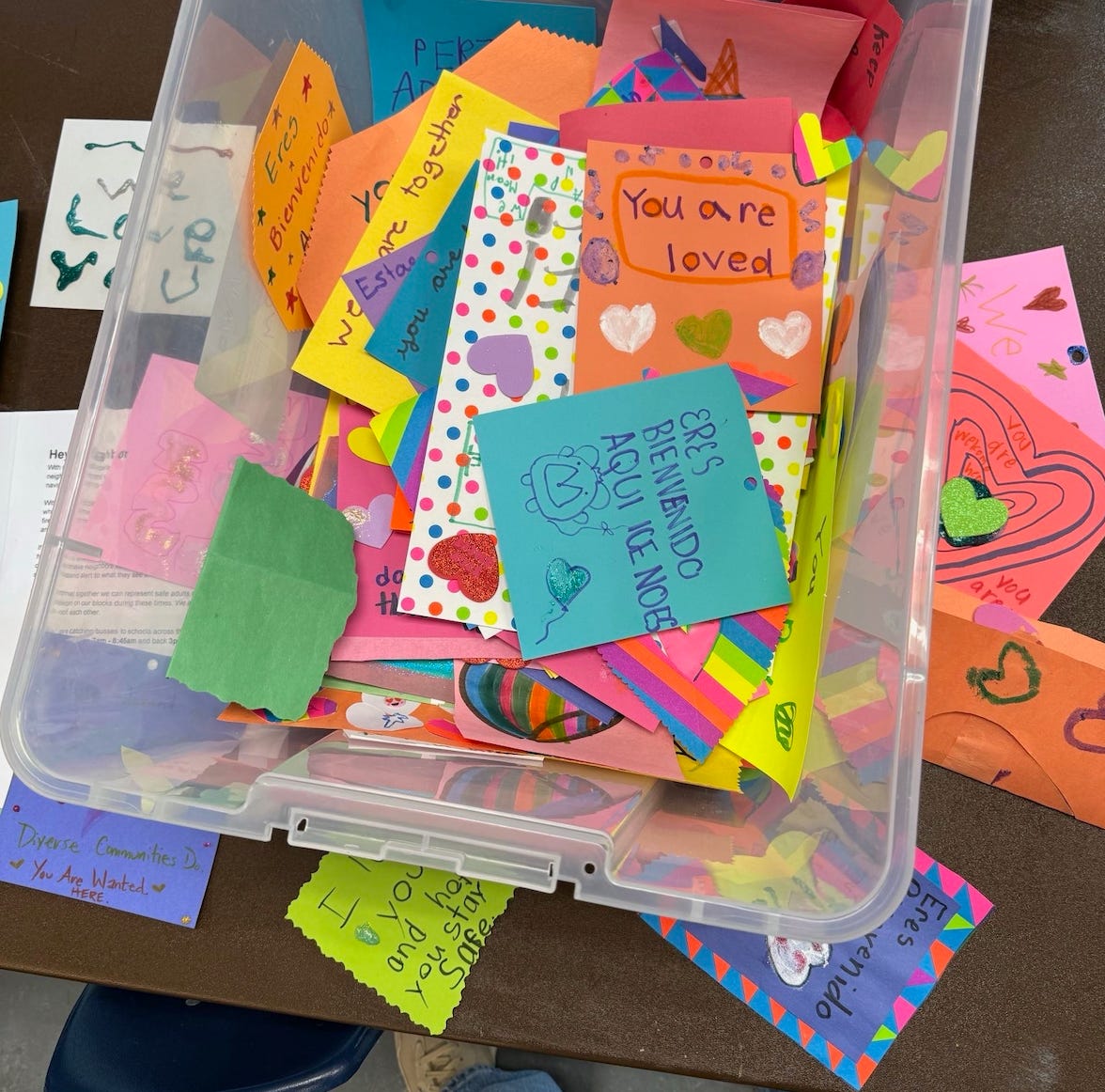

A Sanctuary School Team, as Kim described it, is about meeting needs that already exist and grow sharper under fear: rides to school, food, translation, childcare, presence. It’s about coordination: knowing who talks to whom, where information flows, and how to respond calmly if something happens near a school.

But beneath all of that is something more fundamental. It’s about preserving schools as what they are meant to be: safe places for kids. Places where children can learn and eat and play and are cared for – without fear.

What ultimately pulled Kim in was the clarity of the organizing group she connected with — Minneapolis Families for Public Schools — and their insistence on this point: schools must remain safe places for all kids. Together, they said, we can keep ICE out of schools. And keeping ICE out of schools isn’t abstract or symbolic. It’s practical. Because if schools are protected, communities are protected. To keep ICE out of schools is to keep ICE out of neighborhoods.

Still, stepping into that work wasn’t simple. Kim wasn’t sure how to talk to other parents at her son’s elementary school about it. Although the school is only a couple of miles from areas experiencing heightened ICE activity, it sits in a quieter, more affluent, whiter neighborhood. She worried about being misunderstood – about sounding alarmist, or like someone borrowing urgency from other people’s fear.

But she was surprised to find that it wasn’t hard to get other parents involved at all. On the contrary, people were very ready.

Parents flooded in asking how they could help. People worried they didn’t have “relevant experience” — architects, dentists, project managers — until they realized those skills were exactly what was needed. Organizing a spreadsheet. Coordinating drop-offs. Carrying boxes. Standing on a corner for an hour.

There was a place for everyone. And that’s why it worked.

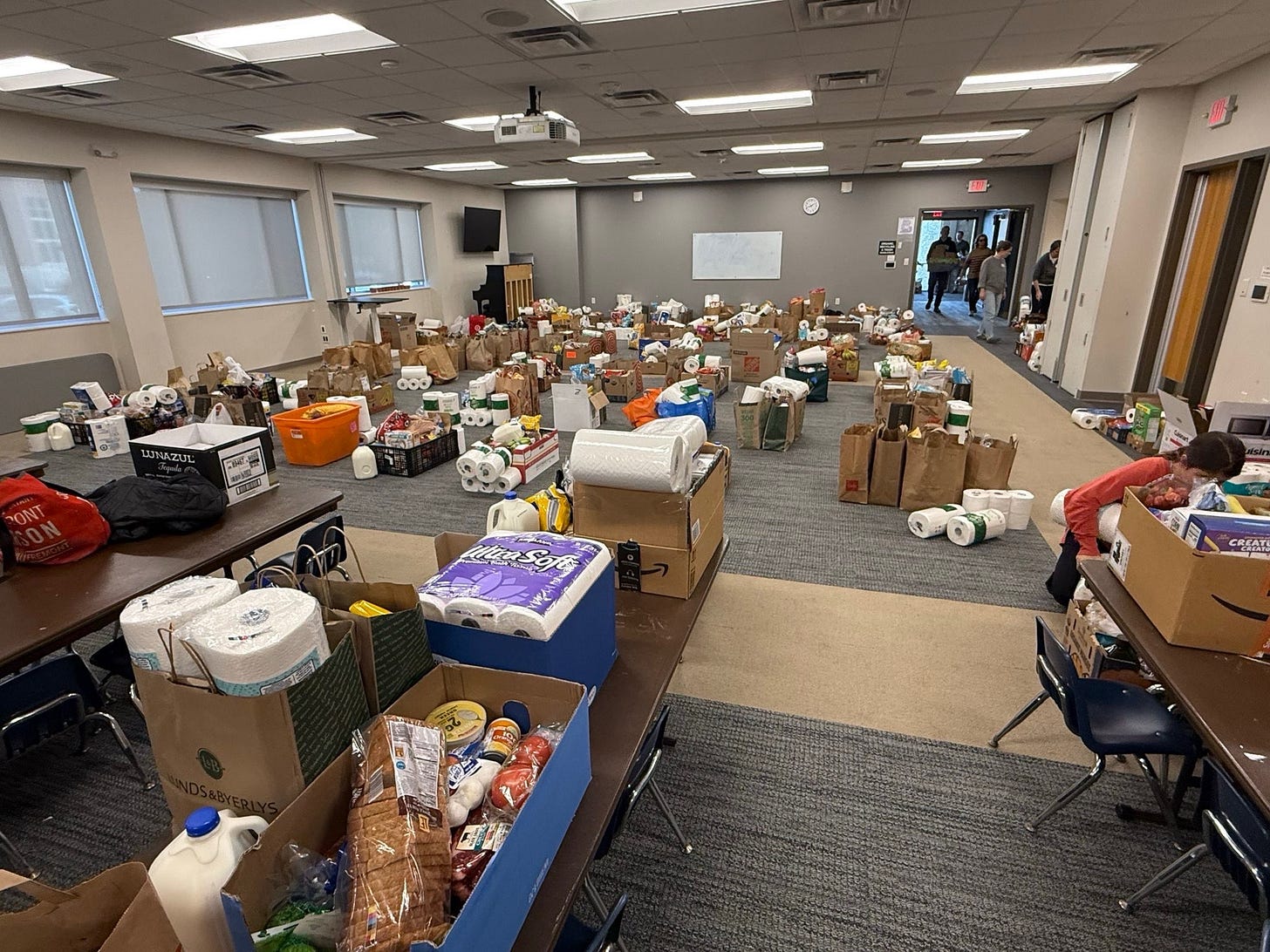

At one point, a nearby school asked if anyone had extra cold storage for donated food. Within twelve hours, two parents offered chest freezers. When another school ran out of grocery funds for families they’d been supporting week after week, Kim’s group put out a call. Within a day, dozens of families committed to assembling food boxes — signing up before they even knew what would be inside them.

“This kind of organizing isn’t glamorous,” Kim told me. “Sometimes it’s just a Buy Nothing group on steroids.” But it works because it connects real needs to real people who want to help, and gives that impulse somewhere to go.

Over and over, she returned to the same point: you don’t need special training. You don’t need to be an activist. You don’t need to speak every language or know immigration law. Translation tools exist. Schools already have social workers and family liaisons who know where the needs are.

What’s required isn’t expertise. It’s willingness. Willingness to show up. Willingness to feel a little awkward at first. Willingness to say yes.

She told me about driving home through Minneapolis at night and seeing parents dotted across intersections — bundled up, wearing reflective vests, holding whistles. Not chanting. Not protesting. Just standing there, visible, so families knew someone was watching out.

That image has stayed with me because it looks so much like the snowstorm. Ordinary people, in bad weather, doing unremarkable things that add up to safety.

When I asked Kim what someone can do this week to get started, she named a few simple steps.

First, she pointed me to 5 Calls, a tool that makes it easy to contact your representatives and say one clear thing: ICE does not need more money. Not for raids, not for detention, not for “enforcement.” Calling once helps. Calling regularly helps more.

Second: support the people already doing the work. Mutual aid groups across Minneapolis are moving food, rides, and resources to families who need them. Find one and donate. Small amounts matter when they’re coordinated.

Then she named something just as important — and closer to home.

Download Signal. Start a small group with three or four people who live nearby. People you trust. People who would answer the phone. Just a way to reach your neighbors calmly if someone needs help.

That’s how this starts.

What Kim is a part of in Minneapolis isn’t unique to Minneapolis. It’s the same muscle we used during the storm — just exercised intentionally and ahead of time. Contact. Care. Coordination.

It’s also not new. Kim was clear about this when we talked: what she’s doing now is built on work that Black and brown communities in this country have been doing for generations. Long before it had names like “mutual aid” or “community safety,” long before it showed up in headlines or toolkits.

She told me about the shift that she experienced in 2020, during the uprising in Minneapolis following the murder of George Floyd. Kim is white, middle-class, and lives less than a mile from what is now George Floyd Square. She had heard the terms coined by Black organizers for years — like “we keep each other safe” — and she understood them intellectually. But she did not really feel them until she was living inside that moment.

What it meant to keep each other safe moved from theory to practice. Neighbors texting each other late into the night. Setting up watch schedules. Sharing food and information. Figuring out, together, how to move through fear, to not abandon each other.

Since then, Kim has learned from organizers across Minneapolis, many of whom have been holding the line for years. She mentioned Marcia Howard, who helped hold George Floyd Square in its earliest days and now serves as the President of the Minneapolis Federation of Educators. Howard is once again guiding teachers and school communities through a moment that will likely prove historic.

The question isn’t whether moments like this will keep coming. They will. The question is whether we will be alone, scrolling in our kitchens, or whether we can build enough muscle now to reach out, to link arms, to get after it together.

If something like this were to happen here — in Hudson, or any small town — readiness wouldn’t look dramatic. It would look like schools that can clearly articulate their protocol if ICE appears near a building. Families who know who to call if they’re scared to drive. Rides, translation, food, and information moving through trusted channels — not through rumor or social media panic.

None of this requires agreement on policies or shared politics or language. It requires agreement on something simpler and more fundamental: kids should get to school safely, and neighbors shouldn’t be left alone when fear shows up at the door.

So if you’re reading this and wondering what to do next, here are a few places to begin:

Ask your school district or school board what the protocol is if ICE appears near a school.

Support local immigrant rights – like Columbia County Sanctuary Movement – and mutual aid groups already doing this work.

Help print and distribute Know Your Rights information through trusted places like libraries, schools, and faith communities.

Offer practical help — rides, translation, childcare, admin support — the work that stabilizes families under stress.

Commit to reliability over intensity. Showing up steadily matters more than showing up loudly.

And if all of that feels like too much, start even smaller, with Kim’s advice. Text three neighbors. The ones you recognize by their coats, their dogs, their kids’ backpacks.

Let’s not wait for the next big blizzard to introduce ourselves to one another. Let’s not wait until fear has already isolated us. Let’s build the network now, awkwardly and imperfectly, with the people already around us.

And that, I hope, is what doing something actually looks like.

Thank you for showing us how we are already doing it what needs to be done. It is in us to connect. It is in us to care. If we can care for each other when mother nature calls, we can certainly do it when ICE comes.

I echo Katherine’s words above, Caitie. You’ve laid out a model through your own work and that of your MN friend and I’m very appreciative. Great piece.