“I don’t know who any of these people are,” my friend said earlier this week, referencing the banners attached to the telephone poles on Warren Street. “I know that they’re honoring people who served, but they don’t reflect the Hudson that I’ve come to know. I want to know more about them.”

There was no judgment in his voice about the banners – just curiosity, reflective and sincere. But I found myself holding my breath as he began to talk, wondering what he was going to say about the banners that honor the families of the Hudson I know.

My friend was referencing the Hometown Heroes banners, the ones with faces of veterans from Hudson, past and present. Of course he didn’t know the names or the faces; he’s been here for just under a year. He moved here and jumped in, immediately joining organizations that do meaningful community-building work. Still, there’s no easy way for someone new to learn about the people on the poles that line our city’s main street.

Before this conversation, I had never thought about how the banners might land for a newcomer. All I know is how they feel to me. When I walk on Warren, I am comforted by the faces of my family members up there, by the familiar surnames of people I grew up with in Hudson. That comfort has become something I hold onto in a place that often feels less and less like the one I grew up in. I told my friend as much and shared some about who the pictures represent and what they mean to me.

When I interviewed for my position at The Spark, we met at the Hudson Roastery. I was quietly thrilled that The Spark founders had suggested that spot – because just above the Roastery hangs my uncle, Jake Martin’s, banner. I remember sitting at the table, nervous, trying to sound confident and prepared. But every time I felt a wave of uncertainty rise up, I’d glance out the window and find his face. I’d run my fingers over the gold hoops in my ears – my great-grandmother’s – and I’d feel steadier. I was reminded that I was home, that I had my ancestors at my back. That I knew Hudson intimately and could run a community organization here.

These banners, to me, aren’t just decoration. They’re anchors. They root me in this place, to a version of Hudson I carry in my bones, even as everything around me shifts.

It’s Memorial Day — a weekend framed as a time to remember. For many of us, it’s also barbecues, summer plans, the end of the school year nearing, and the unofficial start of summer. We joke about wearing white again. But underneath all that, the day carries a weight we often skip over.

Memorial Day began as Decoration Day in 1868, created to honor those who died in the Civil War. But its deepest roots lie in something even more profound: a ceremony organized by formerly enslaved people in Charleston in 1865. They held a parade, sang hymns, and decorated the graves of Black Union soldiers — an act of defiant, loving remembrance.

I didn’t know that part of the Memorial Day story until this week. And learning it pulled me back to the same question I keep asking: when we say we’re remembering, what do we really mean? Whose stories do we carry — and whose have we let go?

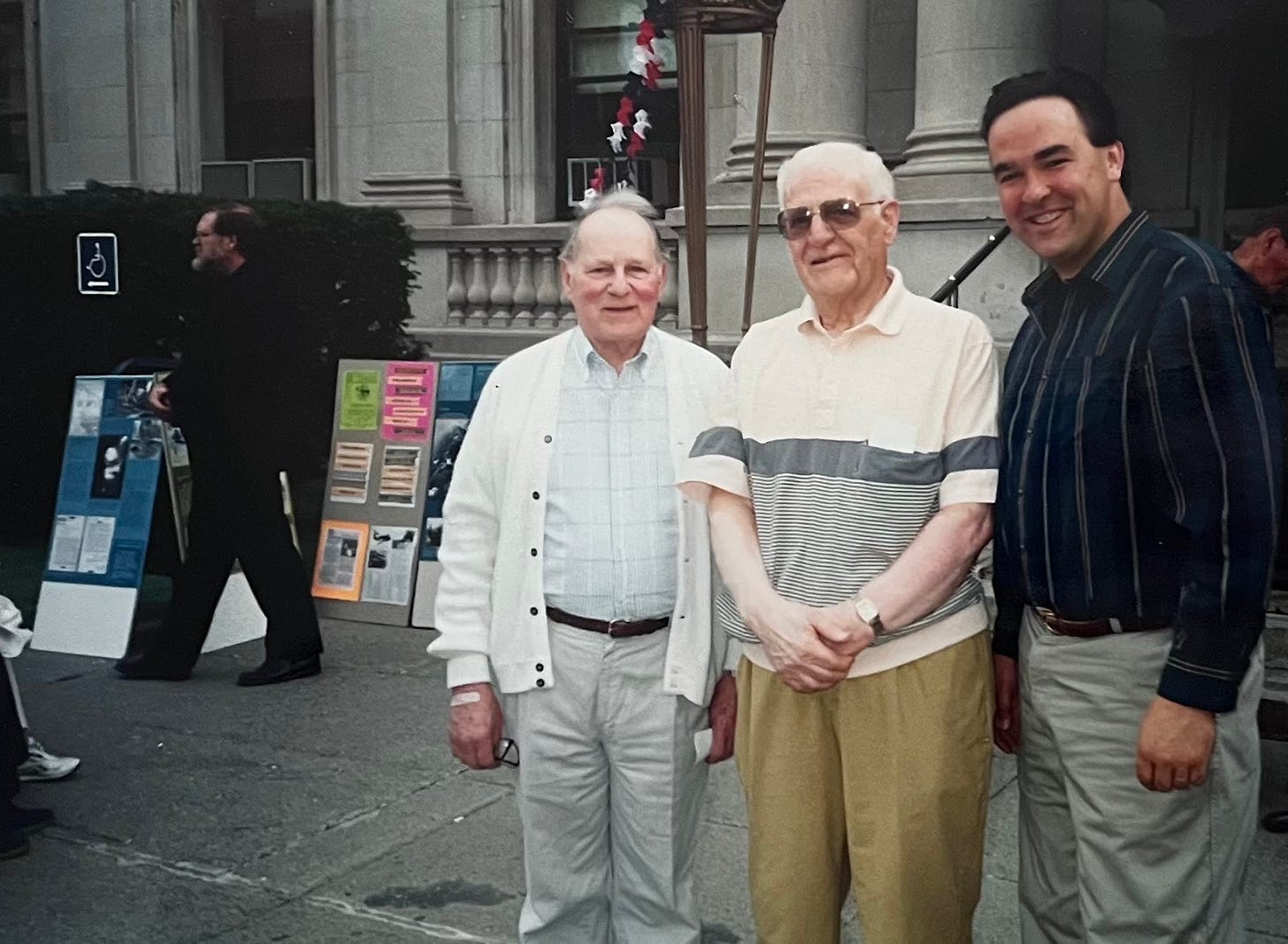

In Hudson, we honor our veterans. I remember going to community events as a kid whose central purpose was honoring and remembering our veterans. My dad, John Hilliard, was County Clerk for 10 years. I dutifully attended every campaign event, community celebration, and awards ceremony happening in Hudson.

And invariably, the organizers would mention our military personnel and our fallen heroes. I remember plugging my ears through the three-volley salute, then running over to try to collect the casings. I remember collecting the poppy lapel pins that everyone wore like they were treasure, begging the other attendees to turn them over to me to take home (flash forward 25 years to me naming my firstborn Poppy…).

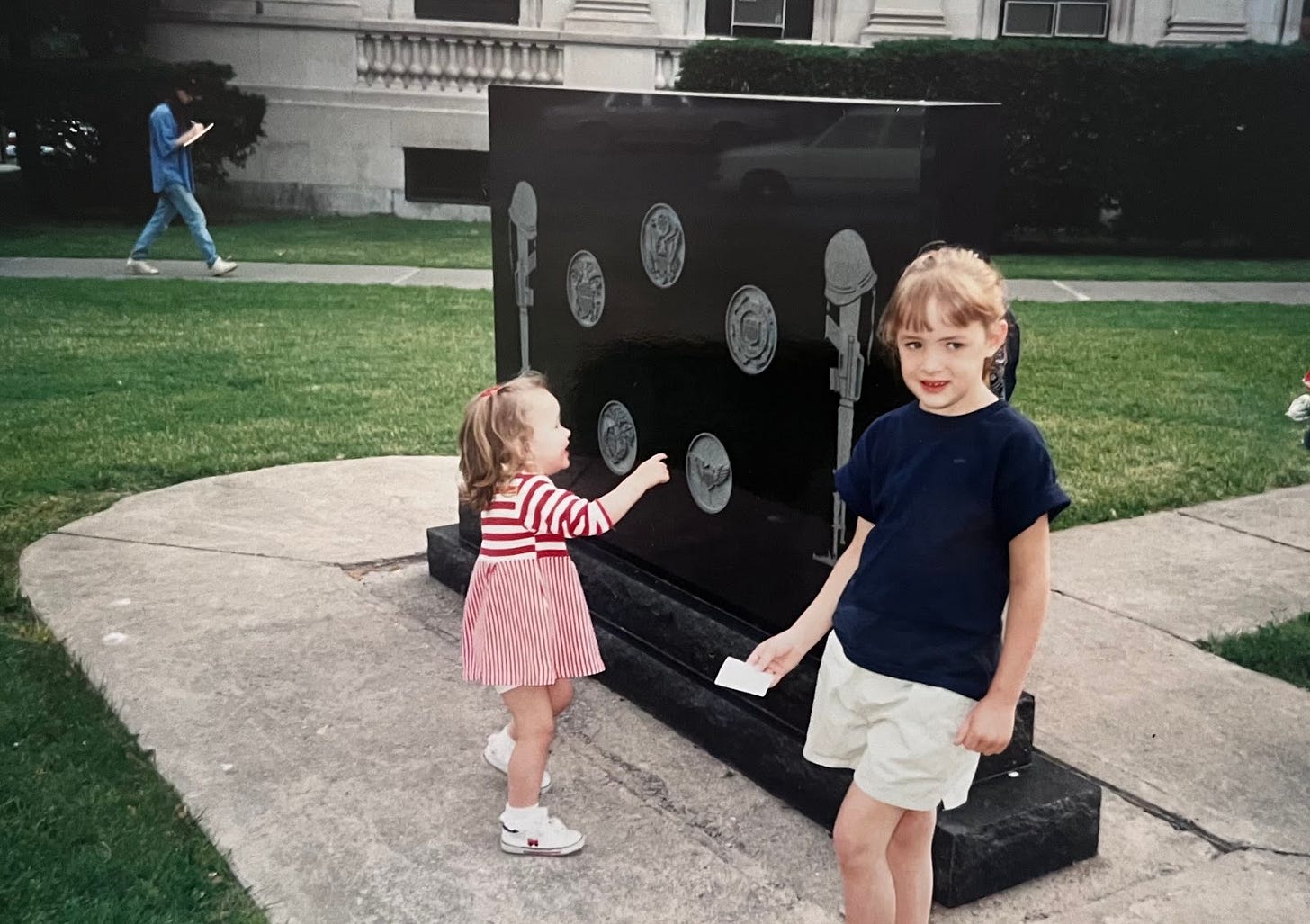

We still have a number of physical spaces honoring our veterans and military personnel today. We have our banners on the telephone poles. There’s also a Veterans Monument in our public square. It was erected “in grateful recognition of the services” of local veterans. It’s somewhat nondescript; a future revitalization of the public square led by the Friends of the Public Square will feature it more prominently within the park.

In front of the courthouse, four distinct memorials stand in quiet formation — each one honoring local veterans from different conflicts: World War I, World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. Their stone faces bear names, dates, and symbols of service.

Cedar Park Cemetery is also home to hundreds of veteran graves. They are the most well-maintained graves in the cemetery, with various people and organizations coming to care for them. Their graves are adorned with flags and plaques. Especially at this time of year, the Department of Public Works spends weeks preparing the cemetery for the influx of visitors on Memorial Day.

I’m proud that these are part of our community, that we physically represent our memories in this way. But now, especially after this conversation with my friend this week, I’m left wondering if these gestures are sufficient. Especially in Hudson, which since 2020 has seen the most significant influx of new people per capita in the country, are pictures and monuments enough to help our community remember?

I think what I’ve come to realize is that remembering is labor. Remembering is telling stories, like my friend and I did this week. It’s sharing that my Uncle Jake, pictured in front of the Roastery on a banner, got his first boat on the Hudson River when he was just a teenager – an old aluminum thing with a small motor that his dad bought him. He built a shack by hand out of salvaged doors where the boat launch is now, near the other makeshift shacks the Madisons, the Wico twins, and the Dotys had cobbled together. It had no electricity, just the sound of the river slapping the rocks. That little patch of riverbank was their sanctuary.

My mom and my aunts adored him – he was the golden boy of the family, charming, tan, always out and about around town or “downstreet”, as I remember him saying. They were heartbroken when he was drafted and sent to Vietnam. He came back quieter. But he still cherished two things: his family and being on the water. Later, when he moved to Florida with his wife, Pat Martin, he spent his time on the water there too. He'd call folks in Hudson often to check in, to stay tethered. The war changed him, but it didn’t erase him. And to me, that’s part of what remembering means – talking about the person, not just the service record.

There is so much more to each person who served than just their time in the military. I have complex feelings about the military-industrial complex. Especially now, when we’re watching unimaginable violence unfold abroad, funded by the very systems that these uniforms represent. But I also believe there’s a difference between honoring the humanity of someone who served and endorsing the reasons they were sent. Remembering a soldier is not the same as justifying the war. And maybe memory is most potent when it holds that complexity, when we allow ourselves to grieve what was lost, and question why it had to be.

And remembering is listening too. It’s being curious, like my friend was, about the stories behind the faces you don’t know yet. It’s taking the time to ask what someone is carrying, and being present when they share it. It’s sitting with those stories, honoring them, and letting them reshape how you see the community around you — especially if it’s one you’re still learning to call home.

This Memorial Day, I wonder what it would look like if we worked a little harder to remember. What if we held storytelling circles? What if we asked veterans what they’d like us to carry forward—what their service meant, what it cost? What if we brought newcomers and long-time Hudson families into conversation, not just across a table, but across time?

What kind of community would we become if we treated memory not as decoration, but as a shared responsibility?

Yes, it takes time. It takes effort. But I suspect it would change us — for the better.

For my part, today I’ll visit Cedar Park, as I often do, to make the rounds with my ancestors. I’ll gather with my family. And this year, I’ll ask them: what are you carrying? What do you remember and why?

And as I walk down Warren Street, I’ll look up at the Hometown Heroes banners. I’ll pause. I’ll wonder. I’ll try to see them not just as images, but as people. Because remembering — truly remembering — starts where my friend started: with a question, with curiosity, with care. It’s how we keep our people with us. It’s how we make sure they’re never fully gone.

This is beautiful. Thank you for sharing. I love the idea of storytelling circles - I absolutely believe we need to actively construct these spaces and these rituals to make sure we do not forget, or fall away from each other.