Housing in Hudson: A Crisis Backed by Numbers

How the data can guide our conversations for a more inclusive future

Hudson is facing a housing crisis. This crisis, much like gentrification in other cities, has been shaped by a combination of market factors, rising property values, and a flood of outside investment. Hudson also had one of the greatest surges of post-pandemic newcomers per capita in the entire nation. The influx of new residents has sparked widespread displacement, with many long-time residents unable to afford to stay in the neighborhoods they've helped build.

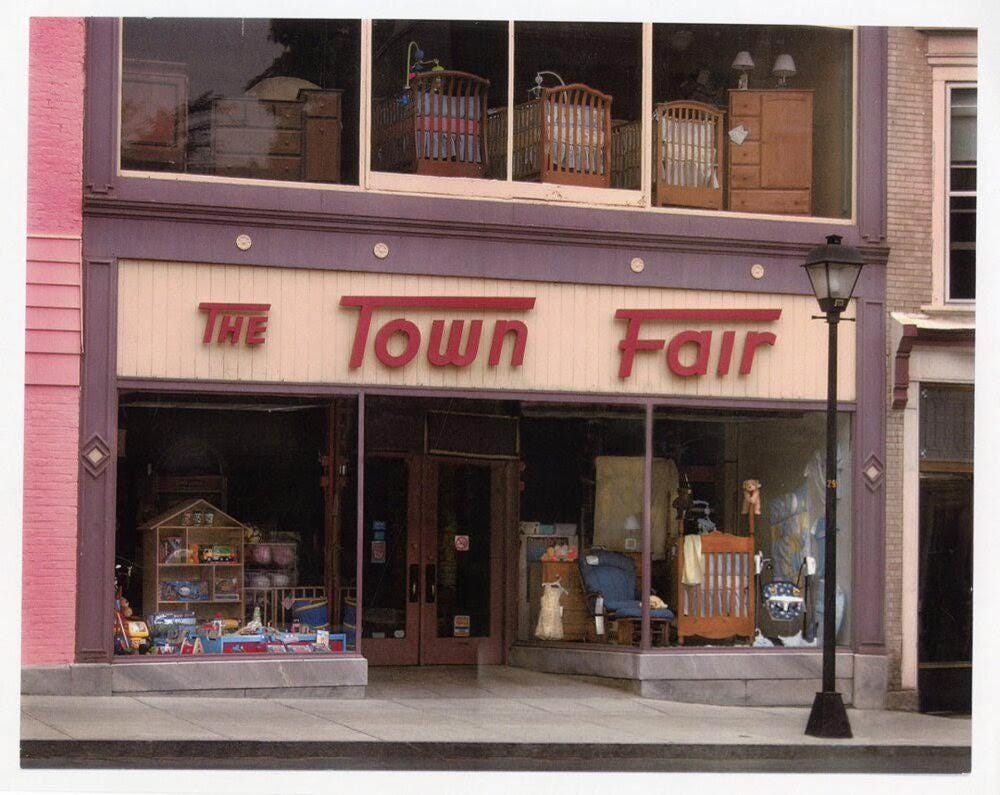

The situation is most clear to me on Warren Street, which is nearly unrecognizable from how it looked during my childhood. For several years, I split time between my mom’s house by Oakdale and my dad’s apartment on Warren Street, in what is now The Whaler Hotel. This building, once home to a mix of apartments, a chiropractor, an attorney’s office, and the Rape Crisis Center, was a living, breathing part of the city. I remember Warren Street as a place where families and kids were always around. I could walk down to the Town Fair, the landmark toy store that had donned the street for decades, and if I was lucky, I could leave with a toy. I was free to walk or ride my bike alone since my parents knew that I would run into someone who recognized me. My parents didn’t worry — they knew I’d always be surrounded by familiar faces.

We still have community in Hudson, one that I’m proud to be part of, but we’re drawing from a smaller pool. Since the 1990s, Hudson’s population has declined by 25%, from around 7,500 to just under 5,600. This shrinking population has meant fewer families, an aging demographic, and a shift toward a population that identifies as white. As the composition of the city has changed, the feeling of who this city is for has changed along with it.

Now, Warren Street, while undoubtedly more attractive, has become a haven for tourists and shoppers seeking luxury goods or artisanal treats. The businesses lining the street have changed, and many of them are now out of reach for working- and middle-class locals. I can’t help but feel that this shift, while making the street more polished, has stripped it of the accessibility it once had for people like me. The street feels less like a home and more like a showpiece – something curated for tourists, not for the community that lives here.

And just as Warren Street has evolved, so has the landscape of housing in Hudson. What was once a city where people like me could live, work, and shop on the same street is becoming a place where only those with deep pockets can afford to stay. A steady stream of wealthy buyers from outside the area is purchasing property, pricing out local families and causing rents to skyrocket. This shift is not just economic. It’s deeply personal for many of us — the people who have called Hudson home for decades or even generations. Historic homes that once belonged to working-class families are now either sitting empty, being flipped for profit, or converted into luxury second homes and short-term rentals.

This housing crisis is not news to anyone who has tried to rent, buy, stay, or come back to Hudson. But we as a community seem unable to find our footing in a conversation about housing. The starkest example of this came during a public meeting I attended several months ago about a grant application for the revitalization of Bliss Towers, a Hudson Housing Authority-managed property that currently houses around 100 families. The room was packed full of people with vastly different perspectives, from residents of Bliss pleading for better housing options immediately to securely-housed community members touting the need to slow down and re-evaluate how we might integrate scattered site housing. The room teemed with emotions — anger, desperation, despair.

I think about that meeting often. Not only for its content but also for how that meeting could have started to foster some understanding of each other as neighbors. I think there is a lot more we can do to encourage perspective-taking and empathy for others in Hudson, especially those who are housing insecure. But to start, we as a community need to get square on what we’re up against housing-wise.

Last month, at a Hudson Industrial Development Agency (IDA) meeting, Hudson Valley Pattern for Progress presented a report on housing in Hudson that laid out the numbers in vivid detail. The report was heartbreaking to read, but it’s been extremely helpful for me in grounding my conversations about housing in facts and data. I’m hoping that surfacing it can be helpful for others so we can move towards solutions.

In the last decade alone, the number of households in Hudson spending more than half their income on housing has tripled. In 2011, there were 195 households in this position. By 2021, that number had jumped to 610. Shockingly, 779 renting households — nearly half of all renters in Hudson — are now paying more than 30% of their income just to keep a roof over their heads. This is a severe indicator of housing instability, and it highlights just how wide the wealth gap has become in Hudson.

Hudson is also losing the types of homes that have historically held our community together — the small-scale, multifamily properties that once housed working-class families. Between 2013 and 2023, the city lost 333 units of multifamily housing — duplexes, triplexes, quads — which were a key source of affordable living. In contrast, only 33 new units were added during the same time period. What this tells us is that Hudson is not adding enough affordable housing to keep up with demand. Instead, the housing we do have is being taken off the market — transformed into second homes, short-term rentals, and vacant properties that serve the interests of absentee investors, rather than the people who live and work in this city.

This situation is especially cruel in a community where so many residents are the very backbone of the city. Hudson’s median rent is now $1,309 per month. To afford that without being considered "cost-burdened" (spending more than 30% of one’s income on housing), a person would need to earn $52,360 annually. But here’s the kicker: although tourism has brought new jobs and industry, the people who work those jobs cannot afford to live in Hudson. Hudson’s food service workers average just over $37,000 per year. Retail workers make just under $46,000. These wages simply don’t add up when compared to the rising cost of housing. So, people are leaving — or worse, they never even have the opportunity to stay.

And who’s moving in? The people filling the vacancies and driving the market are those with significantly more wealth. The average income for newcomers to Hudson is $166,000. The people leaving, the ones priced out, have an average income of $68,000. This is not just a financial gap; it’s a chasm that speaks volumes about the shift happening in our community. And it’s a shift that’s fundamentally altering the fabric of Hudson itself.

Recent Columbia County data on the number of residents without housing altogether paints a clearer picture of just how dire the situation has become. The Department of Social Services reported housing 163 individuals at the end of 2024, up from 130 in January. The increase in homelessness and reliance on motels as emergency housing underscores the severity of the crisis — motels that, while providing a temporary solution, often come with inadequate conditions and services. In just a year, homelessness in the region has risen significantly, reflecting the broader trend of housing instability and displacement.

So, yes — the numbers are clear, and the message is undeniable. This isn’t just a housing crisis. It’s a crisis of belonging. It’s about who gets to stay in Hudson and who gets pushed out. It’s about the people who make this city run — the ones who cook our food, teach our kids, repair our buildings, and care for our community — being priced out of Hudson, and for many, Hudson is the place they’ve always called home.

I am coming to realize that a lot of what I feel about Hudson is tinged with grief. I think a lot about what we’re building here — what we’re preserving and what we’re letting slip away too easily. Grief isn’t just about the loss of life. Grief can be about the loss of place — about watching something you love transform into something unrecognizable. It’s about seeing people leave. It’s about trying to hold on to a future that still includes you and the community that you care about.

We need real solutions. The challenges facing Hudson are complex, but they are not insurmountable. The report touches on this too. We need housing policies that protect affordability and preserve the character of our neighborhoods while also addressing the growing demand for housing. This includes incentivizing the construction of affordable units through tax credits and grants and utilizing underused spaces like vacant commercial properties or abandoned buildings for residential purposes. We need to strengthen protections for renters, ensuring that they are not displaced by rising rents or redevelopment. Policies that preserve our rental stock and prevent the loss of affordable units are critical — especially as housing prices continue to surge. We should prioritize homes for the people who live and work here, not just investments for those who have no intention of putting down roots.

Accessory dwelling unit (ADU) legislation is also on the table in Hudson. ADUs can provide opportunities for homeowners to rent out space to local residents or create housing for family members, helping to ease the strain on the rental market. And as the Pattern for Progress report indicates, we must also explore other options, like land trusts, zoning reforms, and the expansion of public housing programs. Additionally, zoning laws could be adjusted to allow for higher-density housing and more mixed-use developments, which could increase the housing supply without compromising the integrity of our neighborhoods.

I sincerely hope that we can move towards understanding each other as neighbors — people who care about the future of our community. We need to move beyond the division and frustration that often surrounds these difficult conversations. Data like the Pattern for Progress report can help inform our discussions, providing us with the facts needed to make sound decisions. It's easy to get caught up in emotions, but we need to focus on the bigger picture: ensuring Hudson remains a place that everyone can call home, whether they’ve been here for generations or are just starting to build their life here.

Here is the full Pattern for Progress report. Look it over and share it with your neighbors, your landlord, and your friends. Let’s move the conversation on housing in Hudson forward.

This is a fascinating post and I can’t wait to do a deep dive into the Pattern for Progress report later this evening. My husband and I have only lived in Hudson for nine years at this point, but the trends in housing and commercial real estate are really difficult to watch, especially since the pandemic. We’ve remarked to each other more than once that there’s no way we could afford to move to Hudson now; in less than a decade we’ve been priced out of our own city.

I’ve given up any hope of the city somehow controlling the number of buildings bought by absentee investors that are allowed to just sit vacant instead of being used for housing, so it feels like ADU’s might be the best bet. There are plenty of garages and carriage houses that could be fixed up, or people who have enough room in their yard for a nice little one bedroom apartment or two. Extra income, extra housing, it feels like it could be a win-win. The problem with that is building costs. I just don’t see how it could be financially possible to build or renovate and then afford to make the apartments available as affordable workforce housing. My husband and I live in a duplex, my retired mother lives on the other side, last year we took on a building project that at the moment will function as an extension on our side, some extra space we can enjoy, but once she is not able to live alone anymore will provide her with separate living space under our roof, and we can then turn her two bedroom side of the duplex back into an affordable rental. We’ve been met with disdain and weird aggression from nearly everyone in this building process, we were flat out told by one of the local companies bidding on the foundation that there is sometimes an unspoken “Hudson tax” and quotes given to people inside the city are often higher because the people here have (or appear to have) more money and the city is more difficult to work with. We found out a few weeks ago that an element that has been in our engineer/architect stamped plans from day one, and on file with the city for months, is going to have to be rebuilt because it has just now been discovered it’s slightly off code, to the tune of two months of my husband’s and my combined salary. I literally cried when I got that news.

We did months of research before starting this project to ensure that we could afford it before starting something we couldn’t finish, at the moment it is coming in over 200% of the high end of the national average for new construction, and 14 months later we still cannot live in it. This is a project the size of a two bedroom ADU. How can anyone who’s not already wealthy afford to build these additional dwelling units, and then how could they possibly be affordable? On virtually every aspect of this project we asked for multiple quotes from multigenerational local businesses and they were always the highest; I fear that we are in this never-ending cycle, an ouroboros of wealthy people moving into the area and raising prices, and local businesses taking advantage of that, further raising prices just because someone will now pay them, until living even remotely comfortably is out of reach to all but the most wealthy. There are some tax breaks available to people who make workforce housing, but as far as I’ve read those seem to mostly be in the form of PILOT programs available to already obscenely wealthy individuals building large projects as investments. I don’t have solutions, and this feels like it’s become a rant at this point, but I love this town, and this is something that keeps me up at night. I feel like the only solution lies in a large percentage of people agreeing to be less selfish, and I worry that’s a point so far in the rearview mirror culturally that it’s a foolish thought to even have.

We have a shop on Warren street, and rent is so high it’s very difficult to afford to offer affordable merchandise. I’ve made a point of always having something stupid-but-nice in the shop that someone with just a $10 bill can afford; the $9 bags of imported Swedish fish should be $11-12 (that number is about to grow even higher with the new tariffs), but I keep the price low by adding $50 to an expensive antique. The person who buys that $750 champagne bucket is subsidizing 50 bags of Swedish fish, because this shop is my world and I’ve decided they can afford it. I feel like our housing solution lies somewhere along these lines, we need to stop subsidizing wealthy mega projects and concentrate more on helping a middle class family turn that garage into an ADU…but I’m at a loss right now, and my husband is staring at the wall of text I’ve been writing probably with justified concern. So, I’ll just wrap it up and say I’m so glad I found this Substack, and I’ll be diving into the report later. Thanks so much for starting this project!

Exquisite article! I left Hudson in 2015 and would have loved to rerun but there’s no way I would survive there and even before I relocated I didn’t really feel welcome in the local shops. I traveled to Greenport to do my shopping and dining out. My kids even longed to return to Hudson but unfortunately it wasn’t affordable.